Taş Tepeler Project

SPM researchers are involved as cooperation partners in the Taş-Tepeler project (literally: Stone Mounds Project) under the direction of Prof. Necmi Karul from Istanbul University. Several sites equipped with the enigmatic T-shaped pillars known from Göbeklitepe are excavated and analysed by multinational teams. The researchers from Munich are responsible for the archaeofaunas of Göbeklitepe, Gürcütepe and Karahantepe. Dr. Stephanie Emra is mainly responsible for the analyses, which are part of her DFG project “Two river basins, two histories? Orthodoxy and innovation in animal-human relationships in the Upper Tigris and Euphrates regions”. In addition to the archaeofaunas from these three sites Dr. Emra also investigates assemblages from the Tigris region.

Euphrates-Tigris Project

The transition from hunter-gathering to farming and animal raising is one of the most significant changes our species have undertaken. One of the key areas of study for this transition and the emergence of the stock-keeping of sheep, goat, cattle and pig is the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) (ca. 9,700 – 7,000 cal. BCE) and lies in Upper Mesopotamia, in the basins of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Whilst a significant amount of research has been conducted on the beginnings of animal domestication in this region, the complex manner in which domestication arose and the lack of coverage of datasets across this region means that there are still significant gaps in our understanding of this process. These gaps have not allowed for a more localised understanding of the beginnings of animal domestication between the Euphrates and Tigris basin areas which have their own unique geographical and cultural characteristics, but are often grouped as a supra-region. The objective of this project is to chart the change from a human-animal relationship predominately based on hunting through to the initial uptake of animal husbandry within the Tigris and Euphrates basins in the PPN, and to delineate the shared characteristics and differences in subsistence strategies between these two areas. This project identifies three key gaps in the current state of research: 1) limitations from older datasets generated from rescue excavations conducted in the late 1980s/1990s (e.g. Nevalı Çori, Gürcütepe), 2) a lack of sites where occupation continued over long periods of time, which would allow for study of the development and/or uptake of domestic species within a single locality and 3) an asymmetric coverage of published faunal assemblages regarding the two basin areas and the two time periods of interest; specifically, there is currently a lack of published PPNA faunal studies from the upper Euphrates basin and a lack of PPNB faunal assemblages from the upper Tigris basin. This project aims to address these research gaps through the study of faunal assemblages from six case studies 1. Göbekli Tepe, 2. Karahantepe, 3. Nevalı Çori, 4. Gürcütepe, 5. Boncuklu Tarla, 6. Gusir Höyük.

DFG Project “Two River Basins, Two Stories? Orthodoxy and Innovation in animal – human relationships in the Upper Tigris and Euphrates Regions”, directed by Dr. Stephanie Emra

First insights into the genetic bottleneck characterizing early sheep husbandry in the Neolithic period

Staatssammlung für Paläoanatomie München:

Mitogenetic diversity of sheep did not decline in the Anatolian distribution area of wild sheep when sheep husbandry developed in the early Neolithic c. 10,000 years ago, as previously assumed. SNSB and LMU zooarchaeologist Prof. Joris Peters and collaborators could show that matrilineal diversity remained high during the first 1,000 years of human interference with sheep keeping and breeding in captivity, whilst only declining significantly in the course of the later Neolithic period. The results of their study are reported in the journal Science Advances

Modern Eurasian sheep predominantly belong to only two so-called genetic matrilineages inherited through the ewes. Previous research thereby assumed that genetic diversity must already have decreased rapidly in the early stages of domestication of wild sheep. Our study of a series of complete mitogenomes from the early domestication site Asıklı Höyük in central Anatolia, which was inhabited between 10,300 and 9,300 years ago, disproves this assumption: despite a millennium of human interference with the keeping and breeding of sheep, mitogenomic diversity remained invariably high, with five matrilineages being evidenced including one previously unknown lineage. The persistently high diversity of matrilineages observed during the 1,000 years of sheep farming was unexpected for the researchers.

“In Aşıklı Höyük, there were both sheep raised in captivity and wild sheep hunted by the inhabitants of the site. We assume that occasionally managed flocks were supplemented by native wild sheep when necessary, e.g. to compensate for losses due to disease or stress in captivity. One should also consider that people exchanged sheep over wider areas. A possible parallel to such practice can be found in the import of cereal crops to Central Anatolia, which are native to Southeast Anatolia,” says Prof. Peters, interpreting the results of the study.

The different matrilineages or haplogroups are similar to the branches of a family tree. Individuals belonging to a particular lineage show comparably little variation in their mitochondrial genomes, because descending from a common female ancestor. Today, haplogroup B predominates among sheep in Europe and haplogroup A in East Asia. Consequently, mitogenomic diversity decreased later in the domestication process or at the time when sheep farming spread beyond the original domestication region during the Neolithic, a question that had so far remained unanswered.

To address this question, the international team of researchers led by Prof. Joris Peters, State Collection of Palaeoanatomy Munich (SNSB-SPM), Prof. Ivica Medugorac, Population Genomics of Animals, LMU Munich, and Prof. Dan Bradley, Smurfit Institute for Genetics, Trinity College Dublin, investigated matrilineal affiliation and phylogenetic relationships of 629 modern and ancient sheep across Eurasia.

Comparison of Aşıklı Höyük’s results with ancient DNA signatures in archaeological sheep bones from later settlements in Anatolia and surrounding regions as well as in Europe and Middle Asia clearly illustrates that mitogenomic diversity decreased significantly in the ninth millennium before present. One result of this is the aforementioned dominance of matrilineage B in Europe. “We can now assume that this development is due to a so-called “bottleneck” that took place later in the Neolithic period, when sheep farming spread beyond the natural distribution of wild sheep following the early domestication of the species. This bottleneck likely relates to so-called founder effects, in which smaller flocks were consecutively removed from an already greatly reduced sheep population in the course of the spread of small animal husbandry on the way to Europe,” Peters continued.

“Particularly fascinating are the insights gained through the integration of genetic and archaeological datasets. Together with the numerous other mosaic pieces that zooarchaeologists, archaeologists and geneticists have collected over decades, an increasingly coherent picture of human cultural adaptations since the last Ice Age now emerges. Studies like these show that animal domestication is not to be understood in terms of a cross-generational plan, but rather as a process of chance and necessity that has significantly shaped our recent cultural history and accompanies us to this day,” adds Prof. Ivica Medugorac.

Publikation

Edson Sandoval-Castellanos et al. Ancient mitogenomes from Pre-Pottery Neolithic Central Anatolia and the effects of a Late Neolithic bottleneck in sheep (Ovis aries).

Sci. Adv.10,eadj0954(2024). DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adj0954

https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj0954

More complex than previously thought: The history of fallow deer translocations dates back to the Neolithic Age

- An international team of researchers is shedding light on the migration history of fallow deer in Europe using DNA analyses of archaeological fallow deer finds and modern populations.

- Fallow deer was introduced into southern and western Europe since the Stone Age, often by sea. Some fallow deer populations were translocated from Anatolia.

- The complex anthropogenic distribution history of fallow deer populations in Europe raises fundamental questions about the status of today’s populations as native species worthy of protection.

The new study provides deep insights into the shared past of fallow deer and humans and their role in human societies. Using DNA analyses, the researchers can show for the first time where past and present fallow deer populations originated and where they spread with human involvement and settled permanently under their protection.

More than 40 scientists were involved in the study, including the archaeozoologist Prof. Joris Peters, Director of the State Collection of Palaeoanatomy Munich (SNSB-SPM) and Chair of Palaeoanatomy, Domestication Research and History of Veterinary Medicine, LMU Munich. The study has been published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

To the publication: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2310051121

Baboons in captivity in Ancient Egypt: insights from a collection of mummies

Skeletal pathologies in ancient Egyptian baboon mummies suggest health problems due to inadequate nutrition and chronic lack of sunlight. An international team led by the Belgian archaeozoologist Prof. Wim van Neer from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences examined baboon mummies from Ancient Egypt, around 3,000 years old. Apparently, the animals suffered from various metabolic diseases caused by poor husbandry conditions. SNSB and LMU paleoanatomist Prof. Joris Peters, Director of the Bavarian Collection for Paleoanatomy in Munich, was also involved in the study. Prof. Peters is specialist of skeletal diseases in animals and helped to assess the various paleopathologies in these captive primates. The study was published today in PLoS ONE.

For over a millennium, from the 9th century BC to the 4th century AD, the ancient Egyptians venerated and mummified various animal species for religious and ritual purposes. Tens of millions of animal mummies were buried in Egypt’s underground necropolises. In many places, dogs, cats, sacred ibises and birds of prey were worshipped, but there were also burial sites for cattle, crocodiles and fish. Some of them even contain exotic animals such as baboons, Barbary apes and vervet monkeys, which were not native to Egypt. Not much is known about how these animals were acquired and kept.

The researchers led by Wim van Neer examined the skeletal remains representing at least 36 individual baboon from the ancient Egyptian site Gabbanat el-Qurud, the so-called Valley of the Monkeys on the west bank of Luxor. Radiocarbon dating revealed that the animals lived around 3,000 years ago. The mummy collection is kept in the Musée des Confluences, formerly Musée d’Histoire naturelle de Lyon.

Poor husbandry conditions

Most of the baboons examined were in a very poor state of health during lifetime. The animals’ bones showed lesions, deformations and other anomalies.

“We attribute these skeletal changes to the poor conditions in which the baboons were kept in captivity. Chronic lack of sunlight and poor nutrition apparently did not provide the animals with sufficient calcium and vitamin D and caused severe metabolic disorders that significantly impaired their skeletal development. Presumably the animals were kept in high walled, roofed enclosures without direct access to sunlight,” Prof. Joris Peters says.

“Almost all the animals in the baboon population from Gabbanat el-Qurud suffered from these metabolic disorders. We assume that these animals were born and raised in captivity. They were probably bred locally to meet the demand for animals for processional, oracular and other cult purposes,” Peters continues.

Skeletal deformities and pathologies in primates are also known from other animal cemeteries, such as the more or less contemporary Middle Egyptian animal necropolises of Tuna el-Gebel and Saqqara, and the much older Upper Egyptian site of Hierakonpolis (4,000-2,500 BC). The authors note that similar pathologies, age and sex distribution are seen in baboon remains from Saqqara and Tuna el-Gebel, suggesting a fairly consistent mode of captive keeping.

Further research

Additional analyses are essential to find out more details about the husbandry and origin of the ancient Egyptian baboons. The authors suggest, for example, further examinations of the microbiomes in the dental calculus to gain insights into the animals’ diet and the presence of microorganisms in the oral cavity. Genetic data from ancient DNA might reveal information on where the animals were caught in the wild and what breeding practices their keepers were employing.

Publication

Van Neer W, Udrescu M, Peters J, De Cupere B, Pasquali S, Porcier S (2023) Palaeopathological and demographic data reveal conditions of keeping of the ancient baboons at Gabbanat el-Qurud (Thebes, Egypt). PLoS ONE 18(12): e0294934. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0294934

From passerine birds to cranes – Neolithic bird hunting in Upper Mesopotamia

Staatssammlung für Paläoanatomie München

Birds were an important source of food for hunter-gatherer communities in Upper Mesopotamia at the beginning of the Neolithic period, around 9,000 years BCE. This is shown in a new study by SNSB and LMU archaeozoologists Dr. Nadja Pöllath and Prof. Dr. Joris Peters. The two scientists analysed bird remains from Göbekli Tepe and Gusir Höyük, two Neolithic settlements in present-day Turkey, and have now published their findings in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

Besides mammals, ranging from aurochs to hares, or fish, foragers also pursued an impressively large spectrum of bird species in Southeast Anatolia 11,000 years ago. They were hunted mainly, but not exclusively, in autumn and winter – at the time of year, when many bird species form larger flocks and migratory birds cross the area. The species lists are therefore very extensive: At the Early Neolithic settlement of Göbekli Tepe, for example, c. 18 km northeast of present-day Şanlıurfa (SE Anatolia, Turkey), the researchers identified the remains of at least 84 bird species. Dr. Nadja Pöllath, curator at the Bavarian State Collection for Palaeoanatomy (Staatssammlung für Paläoanatomie München SNSB-SPM) and Prof. Dr. Joris Peters, chair of the Institute for Palaeoanatomy, Domestication Research and History of Veterinary Medicine at LMU München and director of the state collection, identified the Neolithic bird bones with the aid of the reference skeletons of the state collection.

The researchers were surprised by the large number of small passerine birds identified at Göbekli Tepe, comprising mainly starlings and buntings. In principle, the Early Neolithic inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe hunted birds in all habitats – mainly in the open grassland and wooded steppe in their direct surroundings, but also in the wetlands and gallery forest somewhat further away.

‘We do not know exactly, why they hunted so many small passerine birds at Göbekli Tepe. Due to their low live weight, the effort exceeds the meat yield by far. Perhaps they were simply a delicacy that enriched the menu in autumn, or they had a significance that we cannot deduce yet from the bone remains,’ Nadja Pöllath comments on her findings.

The inhabitants of Gusir Höyük, another Early Neolithic settlement on the shores of Lake Gusir, about 40 km south of the present-day provincial capital of Siirt, even further southeast in present-day Turkey, had a different approach: When fowling they pursued almost exclusively two species populating open hilly grasslands: the Chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar) and the grey partridge (Perdix perdix). They apparently ignored the avifauna of the nearby floodplains and the lake. Among several hundred fragments from Gusir Höyük, the archaeozoologists from Munich could not identify a single bone pertaining to waterfowl. ‘Gusir Höyük is the only Neolithic community in Upper Mesopotamia known to us that deliberately avoided wetlands and riverine landscapes when fowling, although they were present. Our results suggest that this was a cultural peculiarity of the Neolithic people inhabiting Gusir Höyük,’ said Prof. Dr. Joris Peters. ‘Our comparison of a number of Early Neolithic sites in the region revealed that the sites in the Euphrates Basin share many similarities regarding their meat procurement, while each community in the Tigris Basin seemingly developed its own subsistence strategy,’ adds Nadja Pöllath.

Neolithic settlers of Upper Mesopotamia hunted birds not only for their meat. Some species, such as cranes or raptors, certainly had a more symbolic meaning and served ritual purposes, the researchers suspect. In a future study, they will focus on these socio-cultural aspects of the human-avian relationship.

Publication:

Pöllath, N., Peters, J. Distinct modes and intensity of bird exploitation at the dawn of agriculture in the Upper Euphrates and Tigris River basins. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 15, 154 (2023).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-023-01841-1

Contact:

Dr. Nadja Pöllath

SNSB – Staatssammlung für Paläoanatomie München (SNSB-SPM)

Tel.: 08121 7089 33 oder 08241 911 95 09

E-Mail: poellath@snsb.de

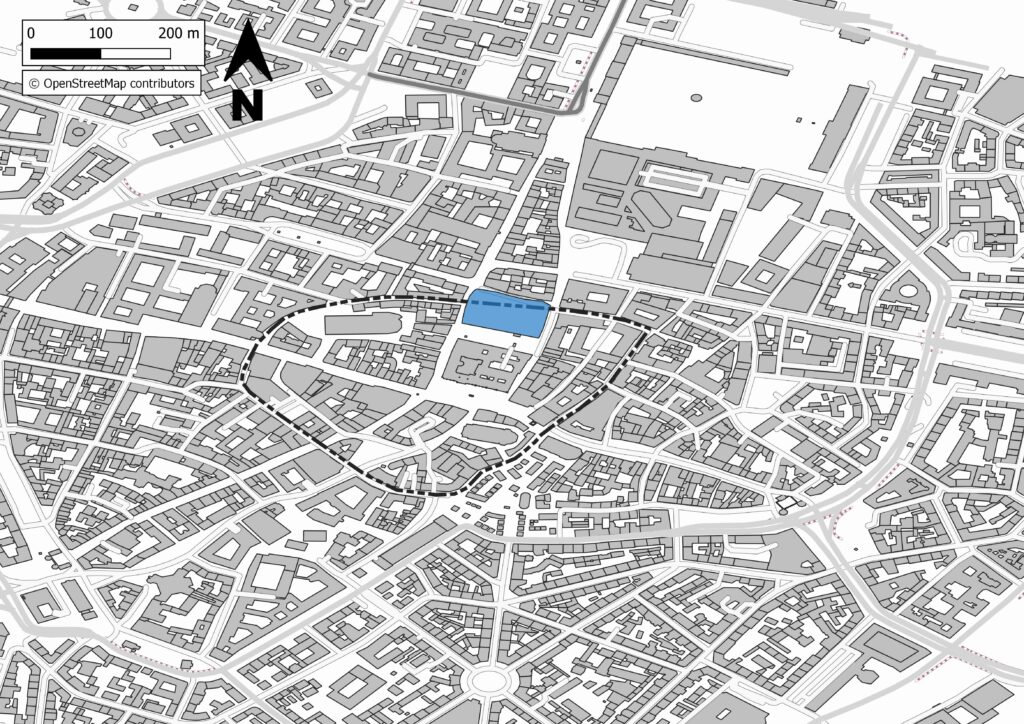

The Great Ditch and the Many Shafts. Archaeozoology of Medieval Munich

Location of Munich’s first medieval city center within today’s city center (dashed line). The excavation area of Marienhof is marked in blue. Created by Ptolemaios Paxinos with QGIS 3.16.8 Hannover using OpenStreetMap. (www.opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl).

The excavations on the “Marienhof” in Munich behind the city hall represent the largest archaeological procedure in the old town of Munich to date. In addition to the city moat, numerous shafts (i.e. latrines, cesspools and wells) were excavated, covering the period from the High Middle Ages to the early modern period. Munich had hardly been explored from an archaeozoological point of view until now. As part of the reappraisal of the excavation project “Marienhof”, this extensive material, now housed in the SPM, has now been examined in detail and published by Ptolemaios Paxinos. The quantity of animal remains from the excavation at Marienhof (> 25,000 specific bone fragments) makes it possible not only to draw statistically significant conclusions about the dietary habits of the city’s inhabitants, but also to shed light on the relationship between the people of Munich and their livestock.

At the time, Munich, like so many other cities in Germany, was a “cattle city”, as the large ruminant was by far the most common farm animal. Pigs and sheep played a much smaller role, but were also valued for their fat, meat and, in the case of sheep, milk and wool. The importance of chickens for the city is surprising. For example, they are the most common animal species in two of the shafts, but they were also significantly more important in comparison with the findings from other southern German cities. The remains of geese and ducks were mainly from domestic fowl with only very few bones of wild relativesAmong the few records of wild mammals, remains of typical hunting game were identified on the one hand (including red deer, roe deer, wild boar, bear), but also skeletal remains of animals that found their way into the pits on their own. These include, for example, the numerous rat bones, as well as the bones of house and field mice.

Most of the bones are slaughter or consumption refuse. In addition, the animal remains also yielded evidence of the use of animal products in crafts. Thus, the numerous cattle horn cores from the city moat clearly point to horn carvers who processed the horn sheaths into useful objects. Written records show that not only patrician and council families, but also craftsmen resided here. Each of the shafts also tells its own story. Two good examples are the two neighboring shafts 1 and 5. In shaft 1 numerous rat bones were found, which, in so far as it could be assessed, came from black rats (Rattus rattus). The clustered occurrence of these rodents in a single finding is an indication that the local residents were dealing with a rat infestation. In Shaft 5, on the other hand, rats are completely absent. Instead, numerous bones of frogs, dogs and cats (partly with traces of dismemberment) were found, but also numerous bones of juvenile and fetal farm animals as well as the near-complete skeleton of a cow. Fallen animals and animals not used for food were thus disposed of in this shaft.

The excavations at the Marienhof impressively demonstrate how, on the basis of extensive animal bone findings, the relationship between humans and animals and aspects of everyday life in medieval Munich can be retraced in great detail.

Literature

Paxinos, P. (2022) Archäozoologie der Abfallschächte: Ergebnisse aus der Ausgrabung „Marienhof“, München. In: N. Benecke (Hrsg.) Leben in der mittelalterlichen Stadt – neue archäobiologische Forschungen. Workshop 29. November 2019, Berlin. Archäometrische Studien 2: XXX-XXX. Reichert Verlag: Wiesbaden.

“Kungas” – the Oldest Equine Hybrids

The Sumerians evidently used horse-like animals in their war campaigns as early as 4,500 years ago. For the first time, a team of French researchers has been able to use ancient DNA analyses to taxonomically classify the earliest hybrid animals bred by humans, which were used in warfare in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium B.C. – and thus long before the appearance of domestic horses in that region. Prof. Joris Peters, Director of the Bavarian State Collection of Paleoanatomy and Chair of Paleoanatomy, Domestication Research and History of Veterinary Medicine at the LMU Munich, was also involved in the study. The scientists have now published their results in the scientific journal SCIENCE ADVANCES.

Horses played an essential role in the history of organized and higher warfare. In addition to horses, the equid family also includes various species of wild donkeys and zebras. While domesticated horses were not used in warfare south of the Caucasus until about 4,000 years ago (Guimaraes et al., 2020), the Sumerians were already using donkeys several hundred years earlier to pull chariots carrying war equipment. One such situation is evidenced by the famous “Standard of Ur,” a c. 4,650-year-old Sumerian mosaic from the southern Mesopotamian city of Ur in present-day Iraq. However, the taxonomic classification of the draught animals used and their relationships have remained a mystery to researchers to this day. On cuneiform tablets of that time, the animals were described as valuable and socially highly regarded so-called “kungas”. A team of researchers led by Dr. Eva-Maria Geigl of the Institut Jacques Monod, Université de Paris, the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, and Johns Hopkins University, with the participation of the Bavarian State Collection for Paleoanatomy, has now solved the mystery.

A study of ancient genes has shown: The Bronze Age “kungas” appear to be the earliest human-bred hybrids between two donkey species, because they were first-generation offspring of crosses between female domestic donkeys (Equus asinus asinus) and male Syrian wild donkeys (Equus hemionus hemippus). The latter became extinct at the beginning of the 20th century.

The so-called ancient DNA analyses – the examination of DNA from ancient tissues, which were carried out in Paris – provided information. For their study, the scientists examined the DNA of equine bones from the approximately 4,500-year-old elite burial site of Umm el-Marra in what is now northern Syria. They compared their analyses with DNA signatures in a c. 11,000-year-old bone of a Syrian wild ass from the Early Neolithic cult site of Göbekli Tepe (Turkey), the analysis and identification of which was performed by longtime Göbekli Tepe researcher and animal bone expert Prof. Joris Peters, director of the Bavarian State Collection for Paleoanatomy (SNSB-SPM) and chair of paleoanatomy, domestication research and history of veterinary medicine at LMU Munich. The last living specimens of the Syrian wild donkeys lived in the Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. Their bones are preserved in the Natural History Museum of Vienna. The ancient genomes of the bones found at Umm el-Marra, as well as their burial in elite tombs, suggest that these hybrid equids correspond to the “kungas”, which were mentioned several times on Bronze Age cuneiform tablets and were considered comparatively expensive, as one paid six times as much for such an animal as for a domestic donkey. With the introduction of the horse in the 2nd millennium B.C. the probably not quite uncomplicated breeding of donkey hybrids became insignificant, since now a domestic animal was available, which, in comparison to the domestic donkey, was hardly inferior to the kungas regarding speed.

(PM) Munich, 17.01.2022

Publication: Bennett, E.A., Weber, J., Bendhafer, W., Champlot, S., Peters, J., Schwartz, G., Grange, T., Geigl, E.-M. (2022) The genetic identity of the earliest human-made hybrid animals, the kungas of Syro-Mesopotamia. Science Advances. Vol.8, Issue 2. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abm0218

Detecting the Problems of Neolithic Sheep Farmers

The study of the remains of unborn and newborn lambs shows researchers the fundamental problems our ancestors had to face in keeping sheep during the early Neolithic period (about 10,000 years ago). In order to draw conclusions on possible causes of lamb mortality in prehistoric livestock farming, it is necessary to accurately determine the age at which the animals died. A group of researchers led by the SNSB has now developed a statistical reference model for such age determination in prehistoric lambs. The scientists have published their results in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

As early as the 8th millennium BC, the first sheep farmers learned that the housing conditions of their animals had an impact on the mortality of unborn and very young lambs. In a study, an international group of researchers led by Dr. Nadja Pöllath, curator at the Bavarian State Collection for Anthropology and Paleoanatomy (SNSB-SPM), and Prof. Dr. Joris Peters, director of the same collection, examined bones of yet unborn and newborn lambs. These were unusually numerous in the findings from the Early Neolithic settlement of Aşıklı Höyük (central Turkey, ca. 8350 and 7300 BC). Over the course of the long settlement duration, lamb survival after birth appears to have improved, while fetal mortality appears to have remained about the same.

The researchers attribute the fact that the mortality of suckling lambs at Aşıklı Höyük decreased over time to improvements in livestock management such as pasturing the herds outside the settlement. The Early Neolithic site of Aşıklı Höyük is the largest and best-studied settlement in Central Anatolia and was permanently inhabited from ca. 8350 BC to ca. 7300 BC. Aşıklı Höyük provides valuable insights into architecture, culture, human and animal nutrition, vegetation, and the development of agriculture and livestock farming in the Neolithic period. While hunting was still important for the meat supply of the inhabitants at the beginning of settlement, livestock farming gained importance later on, with sheep being the most important livestock species. Evidence of abortions and thick manure packages in and between the houses prove that the inhabitants kept their sheep within the settlement for long periods of time.

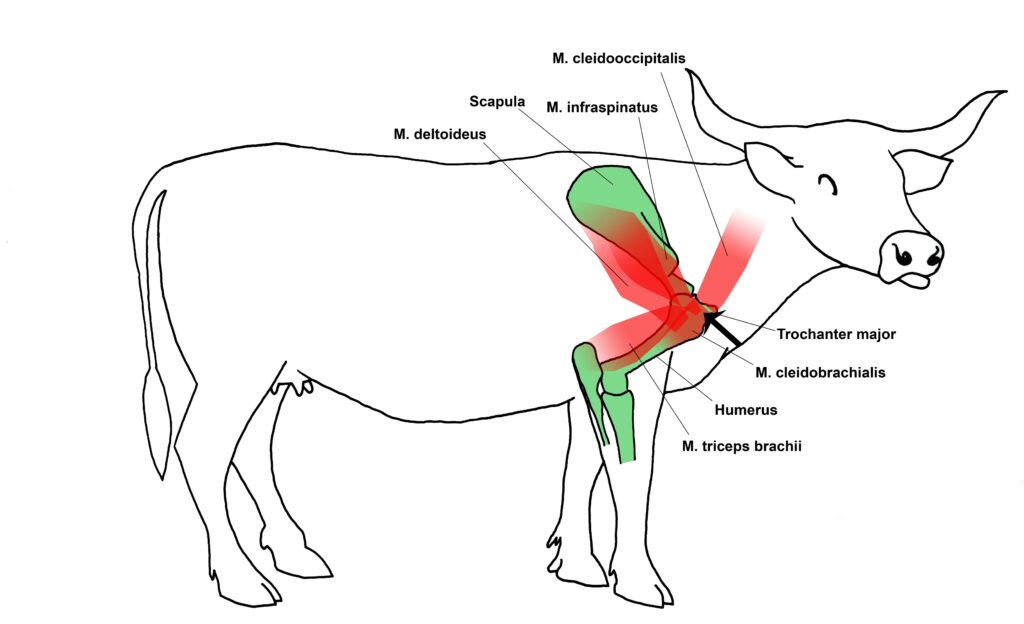

In order to find out what problems Neolithic sheep farmers were confronted with and what measures they took to overcome them, it is crucial to first determine the exact age of an animal’s death. From this, the causes of death can be determined. Traditional methods for assessing an animal’s age of death are based, for example, on the examination of teeth. However, most methods are not accurate enough for distinguishing the developmental stages in young sheep – fetus, newborn, young animal. In this study, Nadja Pöllath and her colleagues developed a new statistical model to determine the age at death of sheep fetuses and lambs as accurately as possible. For the age determination, the researchers analyzed humerus bones from modern sheep of known age in reference collections in the USA, UK, Spain, Portugal and Germany. From this, they created a model that helped to accurately determine the age of prehistoric lamb finds from Aşıklı Höyük. “Our analyses have contributed significantly to narrowing down the causes of mortality in fetal and young lambs. We can now better understand the difficulties people faced during early sheep rearing and domestication in Aşıklı Höyük,” Nadja Pöllath explains. The main causes of death for fetuses and lambs, she says, were infections combined with malnutrition and underfeeding, as well as overly confined housing.

The study was carried out with funding from the DFG as part of the long-term project “The prehistoric societies of Upper Mesopotamia and their subsistence”.

Publication:

Pöllath N, García-González R, Kevork S, Mutze U, Michaela I. Zimmermann MI, Mihriban Özbaşaran M, Peters J (2021) A non-linear prediction model for ageing foetal and neonatal sheep reveals basic issues in early Neolithic husbandry. Journal of Archaeological Science DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2021.105344

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440321000145

Looking Over the Shoulders of Early Neolithic Hunters …

A very special finding is the upper arm bone of an aurochs cow with a bullet wound – found in the backfill layers of one of the monumental complexes at Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Anatolia (Turkey). The shot, presumably aimed at vital organs in the thorax, apparently missed, causing the stone point to penetrate the bone and break off.

As the team of archaeozoologists and archaeologists discovered, the animal was killed at a maximum distance of 30 m either with a bow and arrow or with a spear. Animals of this size were quite intimidating even for experienced hunters, so we can assume that the aurochs hunt was conducted in larger hunting communities. Since aurochs build up large fat deposits before winter, they were probably hunted mainly in autumn in order to build up reserves for the barren season. Autumn is also the time for collecting almonds, pistachios and wild cereals. For this reason, it is also believed that hunter-gatherer groups gathered to hunt together, celebrate together in the time of plenty, and thus strengthen ties within and between groups.

The study was carried out with funding from the DFG as part of the long-term project “The prehistoric societies of Upper Mesopotamia and their subsistence”.

Publication:

Pöllath N., Dietrich O., Notroff J., Clare L., Dietrich L., Köksal-Schmidt Ç., Schmidt K., Peters J. (2018) Almost a chest hit: An aurochs humerus with hunting lesion from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey, and its implications. Quaternary International 495: 30-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2017.12.003.